The Curious Case Of The Extra .2 Seconds

Let’s preface this by saying, I’m a little insane.

This is well known around the Baseball America offices. I’m the guy who timed every single sack in the NFL for five years to see who holds the ball too long or gets rid of it quickly. Two years ago, I got out the stopwatch and also counted frame rates to explain just how hard it is to throw out Billy Hamilton.

You may enjoy the baseball playoffs. You may gather with friends to watch the game, eat some food, have some drinks, have fun.

I was watching Tuesday and Wednesday’s games with stopwatch in hand. Hey, the running games were potentially going to be important in games where runs would be a at a premium, so I wanted to see if the pitchers were fast (1.1) or slow (1.4) to the plate. What kind of pop times would we get from the catchers. How fast were the baserunners going to be from first to second on steals?

You know, just your run-of-the-mill, watching-the-game stuff. OK, I’m a nut and I love some of the arcane details of the game that are easy to fail to notice.

But something was puzzling. Andrew McCutchen was on first base, righthander Jake Arrieta got the sign, got to his set position, broke his hands and came home. Arrieta’s time to home was just under 1.3 seconds. So he’s neither all that fast nor glacially slow.

McCutchen took his lead again, and this time we got to watch his lead as TBS showed the view where we can see McCutchen, first baseman Anthony Rizzo and Arrieta in the same shot. As Arrieta went into his delivery, the shot switched to the normal center field view. Arrieta’s time to home was 1.5 seconds.

Now, 1.5 seconds is glacially slow. A major leaguer who is consistently 1.5 seconds to home is asking to be run on. But normally pitchers are more consistent than that in their times to home. And Arrieta’s delivery didn’t seem that slow.

The next chance to time Arrieta has a runner on, the stopwatch is back out: 1.3 seconds. Then we see the pitcher/first base shot and Arrieta is 1.5 seconds again.

That’s beyond off. But something seems even odder if you’re paying very close attention to Arrieta’s delivery.

I’d love to include a GIF here of the play, but rather than get into an even more arcane discussion with MLB over fair use rights, I’ll post a few .jpegs instead.

Here’s the last frame of Arrieta from the first base angle.

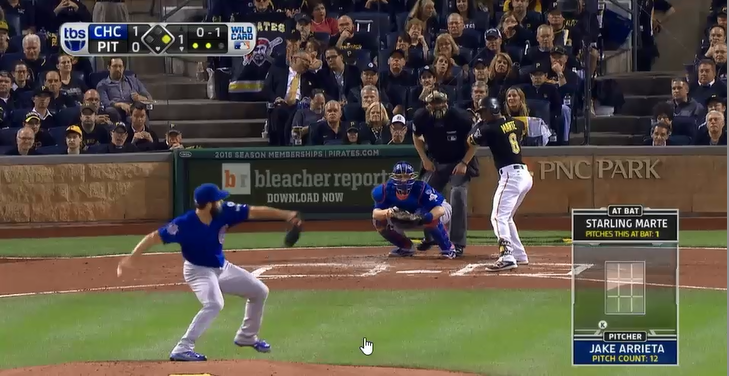

And here’s the next frame from the center field angle.

And the following frame from the center field camera.

Look at Arrieta’s front foot and his glove in this progression. Yes, Jake Arrieta is an amazing pitcher. He combines a plus-plus fastball with a wear-you-out slider and impeccable command. But even more impressively, Arrieta has managed to figure out a way to bend the laws of time and space. How do you hit a pitcher who manages to reverse time in the middle of his delivery?

OK, maybe that’s not the best explanation. There has to be another explanation that doesn’t refute Albert Einstein.

A call to TBS this morning offered something that doesn’t violate the laws of physics: that live broadcast you’re watching, well, it’s a little less live than you think.

The technology MLB uses to serve those virtual ads behind home plate? They require a little pause that refreshes when switching to the center field camera. This is true no matter if it’s ESPN, TBS, MLB Network or Fox Sports 1 broadcasting the game. The Sportvision technology requires the shot to back up .18 seconds to put the ads in the right place. That Bleacher Report ad isn’t actually there. It only exists in bits and bytes and the tech needs a little time to get it served up properly, apparently.

I’m not saying I fully understand why the technology needs a delay. I’m not sure the person explaining it could have explained it any better. But we know enough.

If you see the broadcast cut from another angle to the center field camera during the game, know that you’re actually seeing very briefly the same thing that you saw from the other angle. The “live” broadcast we’re watching is not only delayed by the demands of shooting the video up to the satellite, back to the network, across another satellite to your cable or satellite provider. There’s a potentially additional seven-second delay thrown on top of it to prepare for any unforeseen F-bombs. And then throughout the broadcast there are these almost imperceptible additional delays added in by the requirements of the ad-serving tech.

Does that matter to almost anyone but me? Probably not. But if you’ve got your stopwatch in hand, know that it is enough to screw up your attempts to time. Or hope that it’s a consistent .18 seconds and just subtract it from your time. You may still see me Tweet (@jjcoop36) pitchers’ times to home in the playoffs, but know I’ll have a little disclaimer: objects may be a little faster or slower than they appear.

I shared this discovery with a scout friend of mine tonight. He explained it more simply: “Yeah, you can’t really count on times you get off the TV.”

Now we know why.

Comments are closed.