Imperfections And All, Robo Umps Make Significant Impact

Image credit: (Photo by J.J. Cooper)

At its best, there are moments at an Atlantic League game when you believe you’re watching the future.

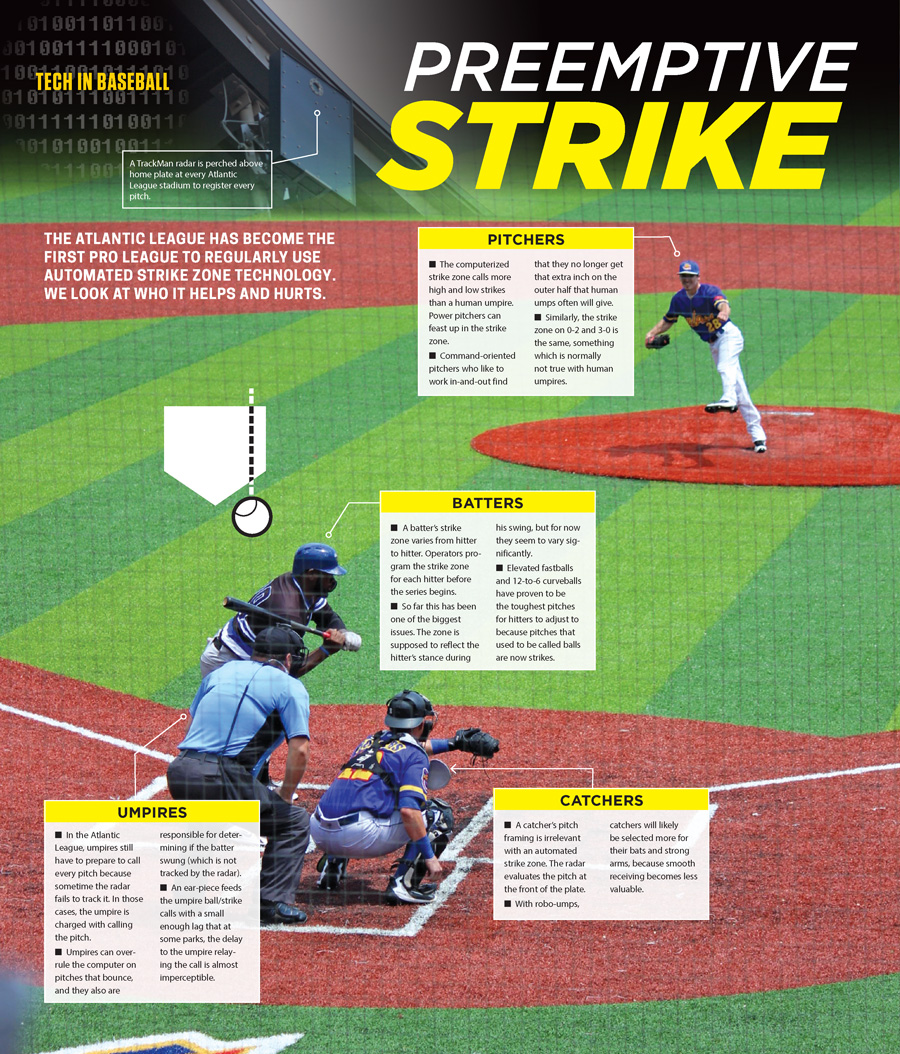

The game hums along and it’s easy to forget that the balls and strikes are not being called by the home plate umpire. The calls come quickly enough that if you didn’t notice the Secret Service-style earpiece, you’d never know that TrackMan’s eye in the sky has turned the men behind home plate into its conduits.

Other times, the future seems far away.

Sometimes it’s a high pitch called a strike even while both the batter and catcher seem a little baffled. Other times it’s a called ball on a pitch that looked like it caught the corner.

The truly frustrating times are when the technology breaks down and the umpire returns to his normal role as the final arbiter of the strike zone. It happens enough that a new set of rules has been implemented—if the ABS (automated balls and strikes) system goes down for two or more batters in one half-inning, it has to be shut down for the other half of the inning as well in the interest of fairness.

When the system works again, the umpire informs both dugouts that the computer has once again taken control of the strike zone.

That back-and-forth is a part of the normal Atlantic League game in the robo-ump era. When the umpire rings up a hitter on a called third strike, hitters often will ask the umpire if he called it or if it was the ABS.

The ABS system is not ready for the major leagues. You can find players who say it’s not ready for the Atlantic League. But if Major League Baseball is ever going to switch to a computerized strike zone, it is going to want to have gotten rid of all the bugs ahead of time.

It will want to make sure that the mechanics of getting the pitches called quickly and accurately are cleared up as well. The Atlantic League’s players are dealing with issues so big leaguers won’t see those problems.

The Atlantic League is serving as MLB’s laboratory. And the experiment is showing that, even if all the imperfections are fixed, adding computerized balls and strikes will make a significant impact.

It will likely change the type of pitcher who has success.

The human strike zone is shorter and narrower than the strike zone hitters now see in the Atlantic League. Atlantic League pitchers are finding that they get high strike calls much more often now than they did with human umpires. In fact, they were getting so many that the league modified the zone, adjusting it down by a few inches because following the textbook definition of a strike was found to lead to nearly unhittable high strikes.

“After the first five or six days, they lowered the strike zone. MLB came back in and changed it. They went below the breastbone and where that line is, the entire ball must be below it. So that part is fixed,” High Point manager Jamie Keefe said.

The new strike zone creates opportunities for pitchers. High Point righthander Michael Bowden’s first pitch of a late July start was a high fastball, high enough that catcher Matt Jones had to bring his mitt above his eye level to catch it. It was taken for strike one. Seeing that called a strike, Bowden went back there for a called strike two. He elevated a little higher on his third pitch for a swinging strike. Six pitches later, Bowden had thrown an immaculate inning: nine pitches, nine strikes, three strikeouts.

The new strike zone has been the downfall of other pitchers. Control artists who focus on widening the strike zone are much better off with a human calling balls and strikes.

“There are some pitchers that will never be able to work (to an automated strike zone). I was never an up-and-down pitcher. I was in-and-out. If in the first three innings I established that down and away pitch, by the fourth inning I got a half inch (off the plate). TrackMan won’t give that to you,” High Point pitching coach Frank Viola said. “Tom Glavine, Greg Maddux and Frank Viola would not have had their careers because those pitches would have been called balls. We would have been walking everyone instead of getting called strikes that forced hitters to swing the bat.

“TrackMan is helping one type of pitcher. It’s a power pitcher who is throwing 95-plus. If he’s over the plate high he has a better chance than anyone else of getting that call. That’s who it is helping. We talk about TrackMan taking the umpire out of the game. It’s also taking the pitcher out of the game. You can be a thrower and still get away with it.”

After just a few weeks, Atlantic League hitters and pitchers have started to adjust to their new normal. Hitters quickly learned that they can’t lay off high pitches, but they also learned that that pitch down and in that used to be called a strike now is a ball.

Adjusting to the unknown has been tougher. The strike zone is calibrated differently for each hitter in an attempt to draw a strike zone that reflects their batting stance when they are swinging (not their pre-pitch setup). So pitchers are throwing to a different zone from hitter to hitter, and those zones are not made available to the teams. There is no process for appeal. Players say some hitters seem to have been given much bigger (or smaller) strike zones than other similarly-sized batters.

More than anything, Atlantic League players and coaches want more data. While TrackMan has been installed at every park (at MLB expense), the teams have not gotten access to that data. Ideally, teams would like to have a visual representation of balls and strikes after the game, so they could get a better understanding of what the computer’s strike zone looks like batter by batter. For now, all of that remains a mystery for players and coaches, although there are hopes that will change.

It’s an experiment now, but a few weeks into the age of robo-umps, there have been no show-stopping issues that would stand in the way of it becoming the new normal.

As multiple players in the Atlantic League have noted, it’s hard to believe MLB would go to all this trouble if they weren’t seriously interested in taking it further than one independent league.

If it does, these first guinea pigs can say they were the trailblazers.

“It’s not ready yet,” Viola said. “Can it work? You can’t say no. But make sure it’s working before you do it. Infants make mistakes. This is in its infancy and it’s making a lot of mistakes.”

“We’re going to get there . . . We are true believers that we can get this right. We have seen the positives it can bring,” Keefe said.

Comments are closed.