North Carolina Leads College Baseball Into The Analytics Age

Image credit: UNC sophomore first baseman Michael Busch

R

obert Woodard used to write down every move and position, and every night he’d relive them all.

What could I have done differently? How should I have responded here?

Woodard wasn’t any sort of math prodigy. He never expected to outsmart or outthink the kid on the other end of the chessboard—kids who could memorize complex patterns and strategies with relative ease. But he knew he could outwork them.

Before he ever seriously picked up baseball, Woodard spent innumerable hours of his youth studying chess. The North Carolina native played in national tournaments every weekend, traveling to far-flung places like Arizona, Arkansas, New York, Tennessee and Florida. In sixth grade, he won North Carolina’s K-6 state competition. That same year, on a national level, he placed 35th.

Through his voracious studying, he reduced the game to five steps:

“It’s very basic,” Woodard said. “Control the center, develop your knights and bishops, castle-protect your king, keep your pawns connected.

“You do those five things every single time—and you play a player who’s untrained—and you’re going to win a lot of games.”

The game of baseball, and its hundreds of thousands of outcomes, is not so easily simplified.

In his eight years as a pitching coach, the now-33-year-old Woodard has spent far too many nights lying awake, replaying moves gone wrong in his mind and finding few answers. There have been so many decisions, so many pitches he thought were the right pitches to call—pitches that his pitchers would execute—only to be poked through some hole in the infield at the worst possible moment. For the first few years of his coaching career, Woodard kept following the baseball traditionalist’s textbook, and the textbook kept failing him.

“At some point,” Woodard said, “you get to a place where it’s not good enough just saying, ‘We weren’t lucky today.’”

So Woodard started studying. Three years ago he read “Big Data Baseball,” a book by Travis Sawchik that explores the Pirates’ use of data to turn around the longest losing streak in North American sports history. After that, he read MLB Network analyst Brian Kenny’s book “Ahead of the Curve,” which delves into the burgeoning field of baseball analytics. Suddenly the game opened up in ways he never anticipated; he saw just how much he still needed to learn.

Woodard brought that curiosity with him to Chapel Hill, where he joined his alma mater’s coaching staff in the fall of 2016 after a stint at Virginia Tech.

That’s when he met Micah.

A warm, affable freshman statistics major from New Jersey, Micah Daley-Harris is exactly the kind of kid Woodard used to play against in chess—the kind of kid who finds comfort in numbers and plays with data like he’s playing an Xbox. Daley-Harris wasn’t skilled enough or athletic enough to stay on a baseball field beyond high school, but his enthusiasm for analytics has been bubbling ever since he attended a one-week sabermetrics program as a teenager. He emailed the UNC coaching staff the second he stepped on campus, asking if he could get involved with the baseball team.

For two weeks, Daley-Harris’ primary role was managing the team’s recruiting database. But at night, he and Woodard would brew cups of coffee and exchange ideas for hours— ideas about defensive shifting, spin rate, pitch framing, pitch selection, pitch tunneling, launch angle, bat path, umpire scouting and more.

“It became very evident to me that we were under-utilizing his talent by typing email addresses and birthdays into a database and putting headshots on recruits,” Woodard said, laughing.

That’s when Daley-Harris started taking on a larger role, when he became the Tar Heels’ de facto head of analytics. Now a sophomore, he voluntarily spends up to 80 hours a week inside or around Boshamer Stadium, leading a team of five students that he interviewed and selected himself. He’s at the field so often that Woodard has threatened to change the code to the front gate if Daley-Harris’ GPA ever falls below a 3.0. In some ways he’s become part of the team. He even shares a house with three players—Kyle Datres, Michael Busch and Brandon Martorano.

“It’s unbelievable; I couldn’t ask for more,” Daley-Harris said, eyes wide, about his role. “I came in here thinking there was a 5 percent chance Carolina baseball would want anything to do with me.”

So far, that’s one of the few calculations he has gotten wrong.

Before we go any further, it’s important to note that this story could have easily ended right here.

There could have been no story at all; no reading about the ways in which UNC has reinvented itself over the last two seasons; no spotlight on a program that is helping to lead the college game into an analytical age.

Mike Fox could have said no to every change that has taken place in Chapel Hill—and no one would’ve blamed him.

In his 20th season as UNC’s head coach, Fox is the architect of one of the most successful college programs of the past two decades. He has led the Tar Heels to six College World Series appearances, including four in a row from 2006-09. He’s one of only four active coaches in the country to have 1,400 wins on his résumé.

When his pitching coach and an 18-year-old statistics student approached him two falls ago about using analytics in his decision-making, he could’ve turned them away and would’ve been perfectly justified in doing so. Fox had hundreds of wins before Daley-Harris was even born. Some coaches would’ve taken the mere suggestion as an insult.

Yet the 62-year-old coach said yes.

“I’ve always tried to be open to whatever can help—whatever can help a player, whatever can help a team—and I didn’t know all the details, but I knew there was stuff out there that was kind of now coming into the forefront,” Fox said. “These students who come to help our program, they’ve gotten into UNC on their own, so they’ve gotta be off-the-charts and creative and brilliant. And if they have a passion for the game—I’m willing to listen to anybody. I don’t care.

“When you go two years in a row and you don’t make the NCAA Tournament—people have said, ‘Why are you so receptive to this? Some big league managers aren’t’—it’s because we haven’t won at the level we want to continue to win at. So I’ll take any information.

“Obviously, it’s up to us what we do with this information.”

As competitive as he’s ever been, Fox grew frustrated after the Tar Heels missed regionals with back-to-back 34-win seasons in 2015 and 2016. If UNC had gone to Omaha one of those years, maybe he would’ve been less receptive. But as he evaluated his own program, he kept an open mind.

Nothing was off limits.

“I got asked questions like, ‘Why do you play your infielders where you play them?’” Fox said. “And my old-school, probably dumb, remark was, ‘Well, that’s where they’ve played for 100 years.’ ”

That changed. The Tar Heels employed data-based shifts from the very first pitch of 2017 and continue to do so now—one of the many fruits of Daley-Harris’ data collecting. UNC went 44-11 last season and earned the No. 2 overall seed in the NCAA Tournament, and the Tar Heels are in contention for the Atlantic Coast Conference crown once again this spring, slotting No. 5 in the most recent Top 25 ranking. The incorporation of data is by no means the reason for UNC’s success, but it has certainly played a factor.

The Tar Heels aren’t the first baseball team to employ analytics. They don’t have the game figured out, and they’re adamant that they still have much to learn. Daley-Harris and his team have 100,000 data points to study and more questions than answers. But the very fact they’re trying at all is significant to the college game.

“I think a lot of credit has to start with Coach Fox, because there are coaches all over the country who want to do more of this stuff, but their head coaches are old school and they’re just not comfortable,” said Kyle Boddy, the founder of the data-driven Driveline Baseball program and one of the game’s most innovative thinkers. “I want to stress how rare that is that someone with so much history in the game—any game really—with that kind of pedigree is willing to make the changes he did. The credit starts at the top.”

Often, the relationship between statistical analysts and baseball lifers is anything but cordial. The Stat Geek vs. The Purist is a battle that has raged for decades in a sport that is notoriously slow to change. Even the Moneyball-era Athletics of the early 2000s—considered by many to be the leader of the movement—faced resistance from manager Art Howe for the methods they pushed on him. After all, Howe was the one who had to face the media and defend the product on the field. The same holds true for Fox at UNC.

Statistically-driven front offices are more commonplace in the major league game now, at least among a cluster of teams. The Astros won the 2017 World Series by showcasing a smarter, bolder brand of baseball. They recorded the final out with second baseman Jose Altuve playing in shallow right field.

But that brand of baseball has only now started to trickle into the college game—and slowly at that. Talk with an analyst for a big league team, and they’ll tell you that one of the first indicators a college team is analytically-driven is whether or not they use TrackMan or a similar radar service. Why? Because to utilize data, teams first need a way to collect it.

A 3D Doppler radar system, TrackMan tracks 27 different data points for every play in a baseball game, including pitch velocity, spin rate and exit velocity off the bat. Of 297 Division I teams, 37 have TrackMan installed at their home ballpark. Of those 37 teams, 28 belong to Power 5 conferences.

Not all of those teams are created equal. Some have gained reputations among the coaching community for using the technology in effective ways; others are still scratching the surface; and still others keep their strategies close to the vest.

Several coaches point to Dallas Baptist as a team that has benefited from TrackMan, particularly when Wes Johnson, now with Arkansas, was the team’s pitching coach. Wake Forest is another program with a forward-looking coaching staff and a creative approach. Using TrackMan and advanced concepts like launch angle, hitting coach Bill Cilento helped hitters like Stuart Fairchild and Will Craig access their power more consistently in games. Teams such as Mississippi, Louisiana State and Coastal Carolina have all seemingly made strides, as well.

At UNC, Daley-Harris and his student-run analytics department have found hundreds of ways to manipulate TrackMan and play-by-play data, arming the Tar Heel coaches and players with binders of charts, graphics, advanced stats and concepts that might not feel intuitive to a baseball purist. Daley-Harris and his team use coding language, like Python, to evaluate huge collections of data points at once and display them in accessible, appealing fashion.

The Tar Heels are only getting started, but they’ve already opened eyes in the analytics community.

“It’s amazing the progress they’ve made there in a year and a half,” Boddy said. “When I went there and Micah showed me his spray charts and everything he had for guys, I was shocked. I was like, ‘Dude, this is better than 25 pro teams.’ I mean, you’re chasing down the Astros and a few other teams maybe.

“They’re leagues ahead of anybody else. I could tell you. I know all the teams that are doing analytics. It’s not even close. It’s a joke. There’s not even a 1B or a 1C. Realistically, there’s not even a No. 2.”

And it’s all because Fox had the courage—and humility—to say yes.

Daley-Harris barely slept the night before he met the UNC coaching staff, rehearsing every point he wanted to make in nervous anticipation. Even though he looks barely old enough to shave, he oozes beyond-his-years wisdom. He wears the passion he has for numbers and baseball in the glow in his eyes and in the frenetic pace in which he talks about both.

He doesn’t lack social awareness; he understands he’s just one small piece of an already well-running machine. He knows his charts don’t win games; players win them. He doesn’t write out the lineup cards; that’s all Coach Fox. Daley-Harris jokes that you can’t stare at a page long enough to hit a home run, and it’s true.

His work with analytics has value, but that value shouldn’t be overstated or understated—and that’s something Daley-Harris wanted to make crystal clear early on.

“My biggest goal was to make sure that we controlled the narrative around it, to make sure it was really clear that we weren’t try to take over; we weren’t trying to change decisions,” he said. “We were just trying to provide (coaches and players) with information they didn’t already have that could be helpful. Everyone here has become very good at managing information long before I got here.”

One of the unfortunate stereotypes surrounding baseball analysts—especially at the pro level—is that they act in secrecy. For some teams, an analyst can seem like the wizard behind the curtain, influencing playing time, lineup construction and strategy without ever interacting with the people in uniform his number-crunching directly affects.

That’s not Daley-Harris. It’s hard to spend any amount of time at Boshamer Stadium without bumping into him. He’s there for every practice, every scrimmage. He’s in the players’ lounge. He’s even participated in fungo golf at the field on off-days. On game day, he sits in the very first row behind home plate. As his roommates, Datres, Busch and Martorano see Daley-Harris’ relentless motor firsthand.

“A lot of the time, we’ll be at home, and I’ll say, ‘Micah, what are you doing?’ ” Datres said. “I think this kid has a 4.0 GPA. And he’s like, ‘Nah, I’m working on baseball stuff.’ It’s kinda funny. He’s always on his laptop working on something.”

All those hours, all that data, all those spreadsheets, all the binders would be useless—trash— if UNC didn’t have a coaching staff committed to using them. Where some teams have split camps between analysts and coaches, the Tar Heels are a united front. In one of the first conversations Woodard and Daley-Harris had, Woodard encouraged the then-freshman to not feel like he “was walking on eggshells” whenever he visited coaches.

A huge reason why UNC has been able to embark on this change in direction is because of strong relationships on the coaching staff. Woodard was a key part of some of Fox’s best UNC teams, and he still holds the program’s all-time wins record. In four years on the mound, from 2004 to 2007, he never lost a single start at home. New assistant coach Jesse Wierzbicki, who primarily works with hitters, helped lead UNC to Omaha as a senior in 2011. Associate head coach Scott Forbes has been part of Fox’s staff for more than a decade and has taken over as recruiting coordinator in the last two seasons.

There’s a dynamic of new school and old school on the staff, but those schools aren’t at odds with each other. Together, UNC’s coaches agreed to embrace analytics as part of their decision-making—and to commit to it. They weren’t going to shift one game and then not shift in another.

“We talked about that—are we going to do this halfway or are we going to go all the way?” Fox said. “Are we going to use our TrackMan at another level? And our video? We felt like we either had to go all in with it or not. We met as a staff, and we looked at each other and said, ‘We can’t go there.’ You have to trust your preparation, and I trust my coaches.

“We did go all-in with it. If we shift, and we give up a hit, we’re not gonna look at each other.”

One of the primary purposes of Daley-Harris’ work is to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of players and teams. But it’s up to the coaches to figure out exactly how to use those strengths and how to improve on those weaknesses. If the data shows a pitcher has a below-average breaking ball, it’s not enough to just tell him to stop throwing it; Woodard needs to be able to work with that pitcher to try to make it better. If analytics indicate UNC needs to use an extreme shift against a particular batter, the coaches need to ensure that their players are prepared to play out of position and know how to turn an unconventional 6-5-3 double play or how to react to a stolen base attempt. Forbes looks at TrackMan data when he’s out on recruiting trips, but only his intuition and experience can tell him if a player has the makeup and the toughness to play at the Division I level.

Daley-Harris’ goal is for his data to be grounded in baseball arguments and easily applicable to the action on the field. Often, the data simply serves as confirmation.

“The analytics describe what makes sense in your brain,” Forbes said. “Like someone might think you’re crazy for having (former UNC pitcher) Rob Wooten throw 18 out of 20 sliders. Well, I’m sure the data would’ve told me I needed to do that. We just didn’t have that data.”

The data isn’t infallible, and there is still an element of gut feel in Fox’s decisions. That’s not going away. He values bunting, stolen bases and small ball strategies, and he incorporates all of that into his game plan as necessary. Intuition still plays an important role in filling out his lineup cards; after all, he didn’t win 1,400 games by accident. The key is communication, collaboration and compromise and understanding that everyone ultimately is part of the same team.

“If you try to chase the glory or the I-told-you-so’s, you’re gonna fail,” Daley-Harris said. “Some of the biggest questions or opportunities are in the disagreements. If I find something in the numbers, if I think a certain pitch is really bad, and (Woodard) thinks it’s really good—that’s huge. We need to know why there’s a disconnect there.

“It needs to be finding the right message. Not, ‘I have my game plan and you have yours, and we’ll see which one wins.’ ”

The last two falls, Woodard and Daley-Harris have visited with UNC’s Sports Data and Analytics club—a club Woodard didn’t even know existed—to recruit students for Daley-Harris’ analytics team. Both years, about 40 students applied. Woodard has watched in awe as waves of kids, some dressed in suits and ties, walked into the Boshamer Stadium coaches offices and sat down with a casually dressed Daley-Harris for interviews.

This is only the beginning. Woodard hopes that 10 years from now, major league front offices will feature executives who once served as student analysts for the UNC baseball team. Daley-Harris already spent last summer as an intern for the Diamondbacks and continues to do assignments for them in addition to his UNC work and school work. He likely will be a hot commodity for major league front offices once he graduates, and the same could hold true for his successor—whoever that may be.

“It would be a shame for this to fade away when Micah left,” Woodard said. “So we’re very conscious of making sure that things are going to stay in place long term, because the game’s not changing. (Analytics are) here to stay . . . These things, we think they’re helpful. I can’t imagine now being at any college program that didn’t have a team of students working in this field, because I think it’s that important. There’s not enough hours in the day for a coaching staff.

“And I can’t write code.”

Woodard is well aware of his limitations; he knows he doesn’t think quite like Daley-Harris does. But that doesn’t stop him from asking questions and studying as much as he possibly can. Where some programs are coy about their analytical strategies, Woodard is open and transparent. Coaches from other programs have reached out to him, and he feels as though he learns with every conversation. He’s not convinced UNC is at the analytical forefront (“I know we haven’t won a national championship,” he said). And he doesn’t want to appear like a know-it-all. He doesn’t know it all. He just wants to help UNC win and stop bad games from spiraling into bad weeks, bad months or bad seasons.

“I’m just trying to sleep better at night,” Woodard said, laughing. “Which I do.

“We don’t ever want to be this fortress of secrets, or look like we’ve got it all figured out. We’re just pushing towards trying to be the best we can.”

That push toward the future requires commitment from every member of the program, from Fox down to Daley-Harris. It requires courage, too, to be able to try something that goes against comfortable, traditional methods. Woodard has found that digging into analytics flexes the same muscles chess used to flex for him—patience, focus, discipline, thinking ahead.

Inspired by a move Cardinals manager Mike Matheny made, Woodard put two chess boards in the UNC players’ lounge last year. Even without any sort of verbal encouragement, players began picking it up and some have found that the game actually helps them think about baseball more analytically. Ace righthander J.B. Bukauskas, the No. 15 overall pick by the Astros in last year’s draft, played before every start he made in 2017.

Woodard and Daley-Harris have started a friendly chess rivalry of their own—the grizzled veteran vs. the whiz kid stats student.

It’s more one-sided than you may think.

“I win like every time,” Woodard said, laughing. “I’ve played a lot more than Micah. I should beat Micah.”

Thankfully for the Tar Heels, experience and math don’t have to be on opposing sides.

Analyze This

To get a sense of just how much information UNC coaches are armed with, they shared with us the following charts. These charts contain actual game data, but the names of the players, teams and programs involved were erased at UNC’s request. This is just a small sampling of the bevy of tools the Tar Heels have at their disposal.

Using non-traditional infield shifts was one of the first—and most visible—changes UNC made as it adopted its analytical approach.

The idea of extreme shifting has been a divisive one in baseball circles, and extreme shifts remain a rarity at the college level. Old-school coaches generally subscribe to the notion that a team’s infielders should spread out and cover as much ground as humanly possible. But an analytical team will play its infielders where the ball is most likely to be hit, even if it means playing them out of position. Using spray charts, UNC categorizes hitters based on their tendencies and creates preset infield and outfield alignments for each batter type. At times, that results in large infield holes that could leave the Tar Heels susceptible to bunts.

But the Tar Heels, and other like-minded teams, prefer to play the odds. More often than not, a batter is still going to swing to his strengths.

“Every hit that you take away with an infield shift, you prevent .7 runs from scoring—we know that,” Woodard said. “Last year I think we prevented 70 or 80 hits. You multiply that by .7, and you’re saving roughly 40 runs. So over the course of 60 games, you’re saving 40 runs, and that’s two-thirds a run a game.

“You start thinking about all these one-run games you’re playing, and it gives you confidence. If you know you’re up plus-50 (runs) on the season, and you get beat on a ground ball, you kind of shrug your shoulders a little bit.”

The Tar Heels began practicing those shifts during intrasquad scrimmages in the fall of 2016, using spray chart data on their own hitters. When UNC started playing real games, Tar Heel hitters couldn’t help but notice how much easier it was to hit against teams that didn’t shift against them.

“Your eyes kind of light up,” third baseman Kyle Datres said. “It’s different. Preseason you see the same layout of the defense every day. And Opening Day, it’s like, ‘I can hit it where I used to hit it all the time!’ ”

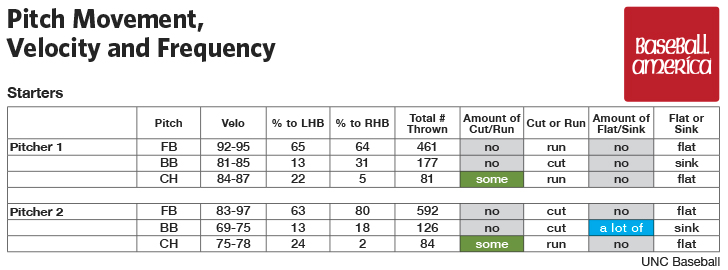

As part of a robust package of pregame reports, Daley-Harris and his team gather and interpret pitch data for opposing teams, documenting how—and how much—pitches move, how fast they are, and how often those pitches are thrown.

That information, coupled with scouting videos provided by a company called Synergy, give UNC hitters an idea of what to expect when they step in the box.

“You know what pitches are spinning or moving,” sophomore first baseman Michael Busch said. “Even if you can go up there with the mindset of, ‘OK, this guy’s fastball two-seams,’ it might give you that three centimeters difference to get you a base hit.”

Equally valuable is the data gathered on UNC’s own pitchers. Daley-Harris has built profiles on each pitcher, with animated graphics that display exactly how each pitch moves out of each pitcher’s hand, which can serve as a valuable diagnostic tool. On one of his first days on the job, Daley-Harris noticed that freshman righthander Josh Hiatt’s spin rates on his offspeed pitches were above big league average. Though Hiatt’s fastball velocity hovers in the upper 80s and low 90s, his other metrics indicated he could be dominant.

Months later, he was named a BA first-team All-American closer.

“My favorite by far is Hiatt—why is he good?” said Daley-Harris, as he pulled up Hiatt’s animated arsenal and traced each pitch with his index finger. “There are a million reasons why he’s good, but for example, his fastball and his changeup tunnel each other and stay right on path, and his slider starts there and sweeps all the way (to the batter’s) back foot.”

By seeing each pitcher’s strengths and weaknesses laid out in front of him, Woodard has been able to more precisely tailor pitch selection. For instance, the data shows that senior righthander Brett Daniels is most effective when he uses his fastball up in the strike zone, one of the few pitchers on UNC’s staff who has that quality. Freshman lefty Caden O’Brien has carved out a crucial bullpen role, in part, because Woodard saw the above-average metrics on his changeup and calls that pitch often.

When Woodard pitched, the general school of thought was to throw 60-70 percent fastballs and the rest offspeed. But if he knew then what he knows now, he said he would’ve thrown his changeup much more frequently.

“When you have an elite pitch, you throttle that up, and when you have a below-average pitch, you throttle it down,” Woodard said. “It sounds really simple, but it can really help with guys being successful.”

After every game UNC plays, Woodard checks his inbox for a carefully curated report for every pitcher who threw, with breakdowns of the pitcher’s velocity per inning, strike percentage per pitch, strike percentage per count and much more.

As seen above, Woodard can dig through each individual at-bat and see how well the pitcher was locating. There’s also a graphical representation of a pitcher’s pace and rhythm, showing how many seconds he takes between pitches; Woodard prefers that graph to be as even and flat as possible, indicating a steady rhythm.

The team also uses TrackMan to monitor the consistency of pitchers’ release points, with each color-coded dot representing a strike, ball or ball put in play; the more tightly clustered the dots, the more consistent the release. In the chart above, the pitcher in question changed his location on the rubber between 2017 and 2018, moving closer to the third-base side. He hasn’t been as consistent with his release point this spring, as illustrated by the 2018 data points being more spread out. According to the red dots on the chart, this pitcher tends to throws more strikes from a slightly higher slot.

Batters receive similar post-game reports, which helps give them direction on what areas they might need to shore up.

“After every practice or scrimmage or game, we can find out what pitches we were hitting well or missing,” Busch said. “And then (Daley-Harris) keeps track of all our at-bats throughout the season and puts them together, and we can figure out what pitches we’re hitting the best and should lay off of, and then we get together with the coaches and work on those things.

“For me, some of those balls inside I’m not hitting as well as the balls away, so I’m trying to focus on not swinging at those pitches. And it’s all because of TrackMan and the information that he’s giving us.”

One of the more cutting-edge concepts in college baseball analytics is pitch framing, an area that UNC is just starting to delve into. The basic idea of pitch-framing is that catchers can “steal” strikes for pitchers (or cost pitchers strikes) based on how they catch a pitch. For example, if a catcher sets his glove below the zone then raises it as he catches the ball, the pitch will theoretically look more like a strike to the home-plate umpire, whether it actually is one or not. The chart to the left is designed to show how many strikes were gained or lost with a particular catcher behind the plate.

Related to strike-zone management, the Tar Heels maintain scouting reports on 115 umpires, displaying how often they call pitches out of the zone strikes and vice versa. That information can give both UNC hitters and pitchers an edge, as strike zones vary much more at the college level than they do in the pros.

Comments are closed.